“I suppose what emerges from inside of us… has a lot to do with our own lives, past and present. From experiences of tumultuous change in my own life, I feel a twinge of what a refugee feels when the world comes tumbling down and life is forever different. And I know a little of what it is to be a survivor.”

Judy Mayotte, Disposable People?

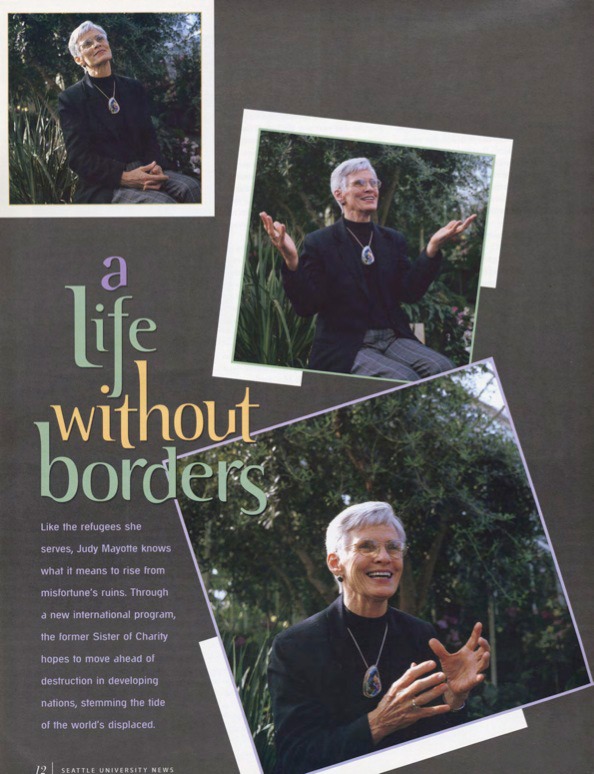

The wheelchair is the second thing you notice about Judy Mayotte — the sleek and sturdy frame cradling slim hips, a flexible seat coming to a stop where her right leg ends, just below the knee. You will notice this in a moment. For now, it is Mayotte’s eyes that rivet you: chestnut oases of laughter and welcome, eyes that could soothe a nation of ravaged souls. It is the eyes that tell her story, not the leg — the leg is but a chapter — and as Mayotte’s story emerges, a lifelong tale of difficulty, disaster and bad luck, the eyes still dance, delight, dream.

Judy Mayotte, you realize, knows worlds more than you ever will about what it means to be a survivor.

Last January, Mayotte returned from a month-long trip to Africa — her first visit since literally risking life and limb during a 1993 relief effort in Sudan on behalf of Refugees International. The tour — through Zambia, Zimbabwe and South Africa — was meant as a site-scouting mission for Seattle University’s International Development Internship program, scheduled to begin this fall.

For Mayotte, it was much more.

“I left my heart and my leg in Africa,” she said, smiling. “So I felt like I’d come home again. Of course, it was a different kind of work than before: now I’m trying to keep ahead of the wars. But I was able to get out into the field for a few days, and it was so good to be out there again among people struggling to help build their societies — doing something positive to build up countries and cultures instead of tearing them down.”

After a dozen years in the international trenches, laboring to repair the human detritus of war. Mayotte is using the International Development Internship program to move ahead of the destruction. Kicking off this fall, the program will dispatch 12 SU students to stable developing countries to work with non-governmental organizations for one quarter, applying their seminar work in service and development in six African and Central American nations.

First conceived in 1997 by then-acting president John Eshelman, the program is Mayotte’s baby — a three-year effort she’s overseen with co-director Janet Quillian, one aimed at grassroots, community-based development in nations on the brink of peril.

“I’ve worked in war zones for a dozen years,” Mayotte says, “and I feel very strongly about the need to go upstream, ahead of war. It’s imperative that we focus on grassroots development; if you have economically sound countries, you have less war. And those of us in the field need to concentrate our efforts there, because foreign policy is moving away.”

Though the U.S. Refugee Assistance budget stands at $625 million this year, Mayotte derides it as “last in the percentage given by industrialized, developed nations.” It’s one of many strong feelings she holds about the flaws in administration policies on international refugees. Like everything in her life, she has earned them.

It was in a Colorado boarding school that Judy Mayotte first experienced Catholicism. Bill Moberly had sent his young daughter to parochial school, intent on an atmosphere of strict discipline. What the non-Catholic Moberly didn’t count on was his daughter “falling in love” with the Church — an unwelcome surprise, says Mayotte, that led him to withdraw her from the school and its teachings.

It would be years before she returned. During her freshman year of college, Mayotte would contract polio. Over the two years it took the young woman to learn to walk again, Mayotte didn’t merely retrace a path of faith: she followed it to the convent.

Her 10 years with the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary took her to the inner cities of Los Angeles, Phoenix, Kansas City, Milwaukee — any community the teaching order led her — and awakened in her a passion for those on the margins of life.

In a handful of years, she earned a doctorate at Marquette University and married a charismatic businessman named Jack Mayotte. The three years they spent together in Chicago — “The happiest of my life, with the love of my life,” she says — would come to a devastating end with lack Mayotte’s slow death from cancer.

A young widow, Mayotte began working as a television and documentary producer, first with public television and later with Turner Broadcasting, picking up Emmys and Peabody Awards along the way. How she ended up drawn to refugee work, she couldn’t say.

“It was just something in my gut, working with refugees. I’d always worked with the homeless, the less fortunate,” she says. “I just decided there was something more.”

When the MacArthur Foundation awarded her a grant in 1989 to write about refugees, Mayotte didn’t hesitate. Then 51 years old, she headed to Sudan, Eritrea, Pakistan, Cambodia, Thailand—two years alone documenting the world’s displaced. The resulting book, Disposable People? The Plight of Refugees (Orbis Books, 1992), remains a standard text on refugee studies. “After the book, I just stayed in the work,” Mayotte says — serving on the boards of the International Rescue Committee and the Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children. She made appearances on public radio and television, testified before Congress on refugee issues.

“And then,” she says with disarming candor, “my leg gets knocked off.”

It had been a fact-finding mission: gathering information on Operation Lifeline Sudan in September 1993 for the 27 organizations working to feed 1.5 million people daily, refugee victims of Sudan’s 30-year civil war. On the trip, Mayotte was accompanied by a film crew from “Visionaries,” a public television series recording the former nun’s relief efforts.

In the final minutes of the resulting documentary, Mayotte and fellow relief workers cross a field outside the rural village of Ayod to meet an aerial supply drop. At their feet, bleached human bones stand stiff amid fluttering grasses, casting a dark silence pierced only by the hum of a descending cargo plane.

What happens next has never been explained: instead of coming in from north to south as instructed, the plane swoops in low in an east-to-west pattern — dropping its cargo not on a painted white X but directly on the relief workers. In the video, the camera whirls as the dozen present begin shouting, literally running for their lives.

When the hail of grain bags is over, an agonizing wail washes through the grass. The camera closes in on the tortured face of Judy Mayotte, her leg decimated by a 200-pound bag of rice that fell an estimated 120 miles per hour. In short order, villagers are dropping AK-47 assault rifles to carry Mayotte to a rescue plane; the relief doctor loses Mayotte’s pulse before reviving her in an airstrip toolshed, Nairobi doctors use aging equipment to rebuild Mayotte’s femur. Evacuated from Africa, Mayotte is flown to the Mayo Clinic, where surgeons agree the upper leg is intact, but her lower leg looks woefully bad. The only plausible option: amputation below the knee.

“It devastates me not to be able to get out into the field,” Mayotte says now. “How do you turn that around?”

Within the year, she was a presidential appointee, a special advisor to the U.S. Department of State on refugee issues; a year later, an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University’s Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. Today, three years after coming to SU and 30 since leaving the Sisters of Charity, Mayotte continues to move the world — one student, one human at a time.

In 1999, an estimated 14.1 million refugees walked the earth — the vast majority of them in the developing world. Defined by U.S. policy as a person who has fled his or her country because of fear of persecution, refugees are brethren to the internally displaced, the additional 25 to 40 million whose homes have fallen victim to war, famine or disaster and who roam their native countries in search of relief.

The numbers of refugees worldwide grows exponentially each year — hungry, shell-shocked thousands shifting from camp to camp in search of sustenance, asylum and a means of return to their beloved homes.

“These are extremely independent people — people who were working and surviving on their own up until the day they fled,” Mayotte says. “In southern Sudan, I worked with a midwife who didn’t even have a clean razor to cut umbilical cords, and I asked her what I should tell people in the U.S. She said, ‘Tell them we’re tired of running, of starving, of bombing and massacres. We stop for water, the bombs break the silence, and we run again.’ It’s amazing who they are in spite of war.”

Mayotte despairs at the growing number of the world’s refugees, strict First World definitions that limit refugee funding and an international climate that can be less than welcoming to its unfortunate neighbors. For her, the International Development Internship is a vehicle for reaching the disadvantaged before disaster erupts.

“I know hatred and factions exist, but more wars come out of poverty than anything else—the absence of viable land and resources,” she says. “Leaders use those circumstances to ignite smoldering embers, and we in the international community — and they make me so cross — allow them to act with impunity. In Iraq, for example, it’s the women and children, the sick and disabled that suffer most. Saddam hasn’t missed a meal, I’m sure.

“Yes, there will always be prisons and torture, but I do think we help facilitate those who are not taking responsibility. And we participate more reactively in forming our policies on refugees and developmental assistance than proactively. We still think in a war and weapons mentality, of destroying instead of building and creating. I feel like we’re only beginning as a people to say how to prevent these situations rather than just reacting to them, but it’s going to come gradually.”

The program’s overview captures the impact Mayotte and Quillian hope to make in students, and in turn, on the developing world: “An experience which fosters combined academic and personal understanding of issues relating to development and social justice will provide a more powerful transformational element and strengthen commitment to these important issues over a lifetime.”

Mayotte puts it more simply. “Students may not choose this work as a profession, but they will come out better global citizens.”

Next year, Judy Mayotte will return to Marquette, this time as a teacher, while Quillian single-handedly oversees the program. While she is happy in her Issaquah condo, Mayotte says, there is something that remains on the more in her — something that can’t be contained by misfortune or borders. Though her life is far more comfortable, it quietly mimics the lives of those she serves: one of tragedy and hope and persistent mobility.

“Despite everything I’ve seen, I still believe in the goodness of people,” she says, eyes afire. “Among the refugees. I’ve met some of the most magnanimous and respectful people in the world—people forced to run for their lives, but who still had hope. And that’s my greatest wish: that we move past borders of land, past borders of the mind.”