Six years ago, Seattle University’s creative writing program didn’t exist. Today, it’s flourishing — drawing new students and acclaimed writers to campus, and capitalizing on its location’s literary cachet.

A movie of winter licks at the picture window, spongy snowflakes painting a precise pattern of confusion within a frame of henna walls.

In the candlelit dining room, a ham bone lays naked on a greasy platter, the stark centerpiece of a ravaged buffet. The students have been here, and as at the makeshift beverage bar in Edwin Weihe’s study, have consumed all that was offered and moved on. Sated, they lean now against a sideboard, ease spines against door frames, rest hip-to-hip on comfort-worn couches and chairs.

Applause swells, and framed by the picture window and its living veil of February snow, Seattle poet Ed Harkness rises to read aloud from his recent book — verse upon verse of loss and longing. Barely a stanza in, a young man in a bowler and coattails closes his eyes, drops chin to chest, and the room of students silently follows: 50 heads bowed in reverence to Harkness’s words.

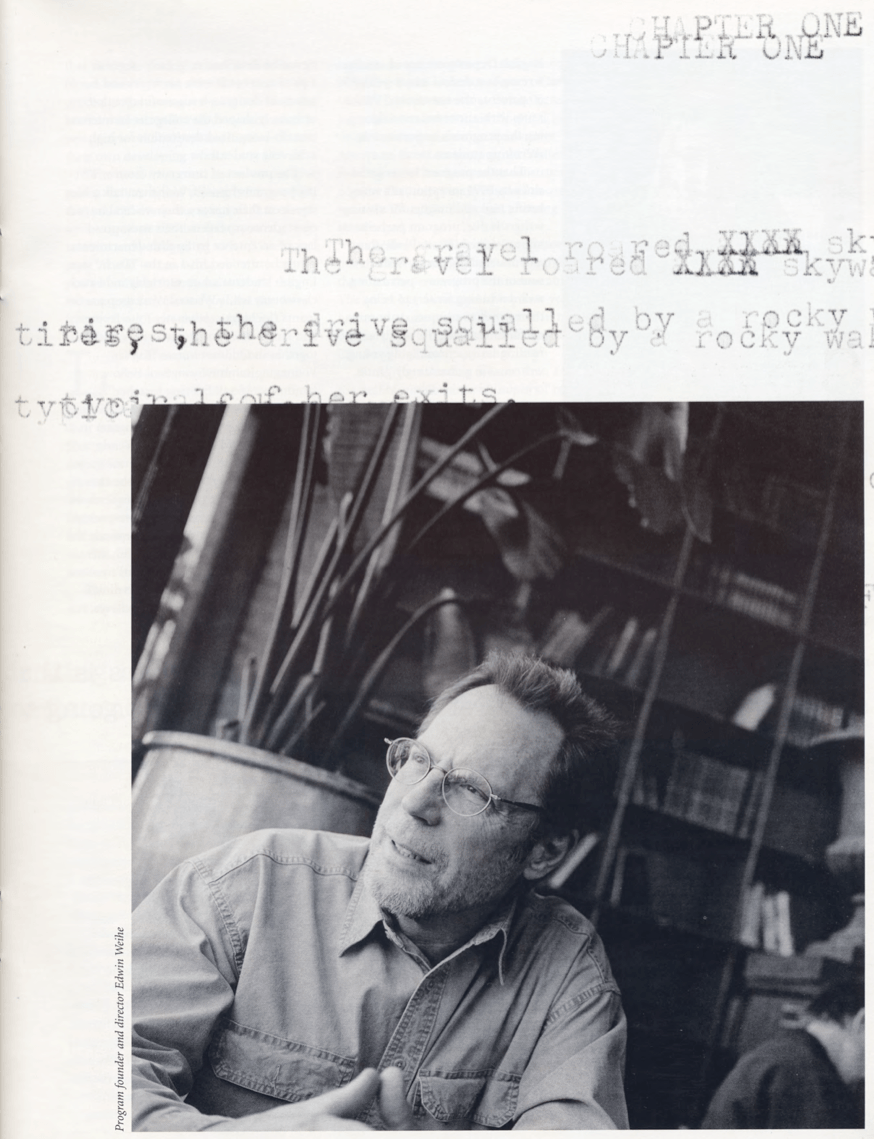

Weihe would rather sit and listen, but the house is distracting him. He swings open French doors to the too-warm Madison Park home, shushes a teenage daughter laughing into the kitchen phone, plucks a grizzled little dog from underfoot. The annual reception for his students in Seattle University’s Creative Writing Program — where young writers mingle with faculty and acclaimed local authors — is all too like his role as the program’s director, fussing over details and machinating behind the curtain to ensure the words are heard.

Just six years ago, there were no students: no pierced poets, no loud-haired but quietly dreaming fiction writers chatting up Weihe’s Germanic-named daughters and being asked to read their work. There was Weihe and poet Ken MacLain, each teaching one poetry or one fiction class on alternate years, and a solidly entrenched English Department that saw little need to nurture writers.

What this is, Weihe says, his hand sweeping across his living room on this snowy Thursday night, is remarkable — a happening drawing the living writers we study, and the students we one day may, to SU.

What this is, he tells you, is a revolution.

In her native Austria, Verena Kuzmany — a soft-eyed and accent-free brunette — was a stage actress, a skill that serves the SU freshman well at readings. At Weihe’s reception, she is certain and composed, her poetry betraying a sageness and experience her years do not. “Writers tend to be free thinkers and liberals, people with a dream,” Kuzmany explains later. “I think this is visible in the young people who choose creative writing as their major here. There is, however, a distinction between those kids who just want to explore—or play around with—their own creative abilities and those who already have a distinct voice of their own, more clear defined thoughts of their own and who feel the need to write. I think I have always expressed myself best in writing, and I do think I have something to say.”

Kuzmany is one of 70 current majors in the program, and counts herself among those who came to SU specifically for its Creative Writing Program, “very excited about the possibility of taking writing classes for different genres each quarter, which is something I’ve enjoyed tremendously so far.”

It doesn’t surprise Michael McKeon, SU dean of admissions. “The most exciting thing for us is that the program is drawing students from around the country, and from outside the country—creative high achievers. And we don’t even have numbers on how many pre-majors the program is attracting.”

What admissions can confirm is that, of this year’s applications, half of those potential SU students expressing interest in the English Department noted creative writing as a desired major — “that’s 50 percent, one out of two,” Weihe notes with astonishment — signifying the program’s importance in recruiting students.

That the program has erupted since its 1994 inception as a marketing tool and magnet for visiting writers is due, program participants say, to Weihe himself. Blade-sharp and disarmingly frank, Weihe is the soul of the program — persuading award-winning writers to bring their words to campus, drumming up funding through a highly visible reading series, encouraging young writers with a charmingly gentle critique. As senior Bryan Miller says, “I don’t think you could have something like this with any other director, or in any other department. We’re lucky to have Dr. Weihe’s passion and dedication working for us.”

A graduate of the University of Iowa’s famed Writers Workshop, Weihe arrived at SU in 1973 fresh out of graduate school. Just three years later, he was tapped as director and founding dean of Matteo Ricci College, an experience he describes in its early stages as a persistent battle with naysayers and reluctant donors — a successful one that ultimately shaped the college as an internationally recognized destination for high-achieving students.

The product of university creative writing programs himself, Weihe can talk a blue streak on their history, their visceral impact on students as readers, their widespread lack of acceptance by English departments. When he attended Iowa in the ’60s, he says, English students sat comfortably in heated classrooms while Writers’ Workshop participants (including classmates John Irving and James Tate) and guest writers huddled together in Quonset huts — “Kurt Vonnegut, Ralph Ellison, Saul Bellow, famous people all freezing together.”

The experience served Weihe well when designing the creative writing program in 1994 at SU, helping him to dispel early opposition to the program and draw English department faculty into the curriculum. Today the program offers seven to nine classes per year, including two poetry courses, and is beginning to incorporate the work of visiting writers into English literature class syllabi, enabling students to relate to the works they study in a three-dimensional world. The result, Weihe believes, is that through viewing writers in flesh and blood, making them more interested in the process and showing real people behind the books, students will walk away with a fresh perspective on Shakespeare, Conrad — and their own developing work.

“The most important lesson we can give young writers is that writing is hard as hell, that you fail every day at it, and that every writer understands that today you’re going to write and you’re going to fail,” Weihe says. “And if we can bring writers to campus who affirm that, and also reveal the tremendous success and joy that can come from writing, we’re doing a good job.”

Last February, several hundred students, campus community members and guests packed Wyckoff Auditorium, sitting in aisles and crowding door frames to witness a literary reading by Sherman Alexie. Acclaimed for his moving depictions of the Native American experience, Alexie joked with the group about Smoke Signals, his 1997 novel (and later, the film he wrote and directed), Hollywood, and the lamentable life of the literary novelist. The crowd hung on every word — and kept him an hour later than scheduled.

The list of a dozen or so authors who participate in the program annually explains its standing-room status: novelists including David Guterson, Robert Clark, Ursula Hegi; poets such as Denise Levertov, John Ashbery, Lawrence Ferlinghetti; playwrights, award-winning screenwriters. Always an event on campus, the Writers Reading series has become so consistently popular that next year Weihe will move the venue to Campion Ballroom, allowing it to be televised.

As Miller says, “The benefits of meeting living writers, hearing their work spoken in the voice that created it is immeasurable. The series has developed in my four years here, and is one of its major assets, in my opinion. The things I learn at those readings I couldn’t learn any other way.”

But Writers Reading is more than a perk for students: it’s a very public way of reaching out to a regional writing community. In Seattle, where writers abound and everyone has a favorite bookstore, the series has become a serious contributor to the literary scene, as well as a very public way of capitalizing on its setting.

“This is a city of writers and readers — and a place that, in particular, is viewed as a haven for writers,” says admissions dean McKeon. “When Frank McCourt writes a book, his first stop is New York, and his second is Seattle. People here expect literature, expect art and music. The SU program allows us to take advantage of our setting, and it’s something we’re looking at in terms of niche marketing.”