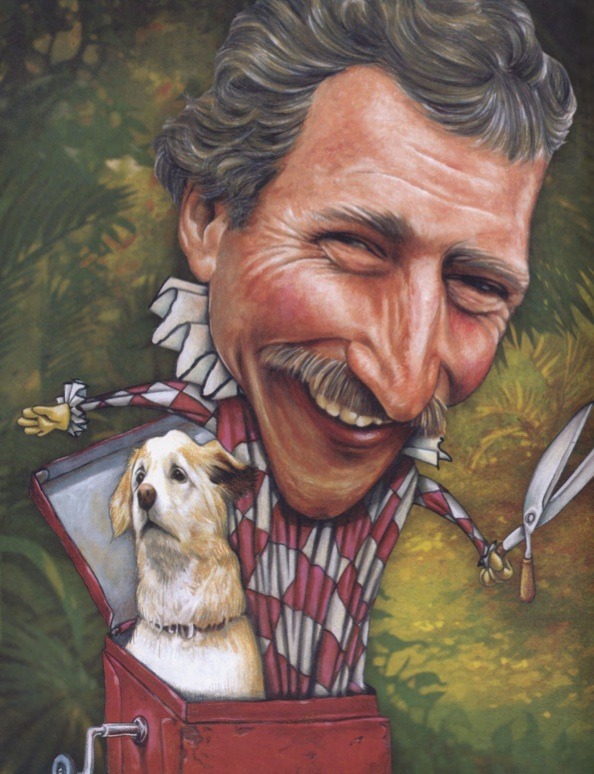

After 24 bounteous years, the wacky and wonderful Ciscoe Morris uproots from Seattle University to till the soil of his media career.

In grey mid-January, when the rose bushes sagged with memory and the Weeping Sequoia cried buckets, the news crews descended on campus, flying to keep up with the man who speaks exclusively in exclamations.

“I love it!” says Ciscoe Morris, ’82, Seattle University’s Director of Grounds and Landscaping. “People ask, ‘Aren’t you camera shy?’ and I can’t stop laughing!”

For the university, and for Seattle itself, the occasion marked the end of a riotously fertile season: after nearly 24 years, Ciscoe, the man who defined “local gardening celebrity” had publicly announced he was trading the outdoors for the interiors of television and radio studios, hanging up the shears and settling in with a USB connection.

With plans to focus on writing a long-dreamt gardening tome and step up his area television and radio appearances, Ciscoe was leaving the sanctuary of SU, the urban garden he envisioned and built — branch by blossom by bug.

“Everyone thinks I’m totally retiring, but I’m not!” he insisted. “I’ve got classes and gardening shows to do, and I’ve already had three calls to give campus tours. I wanna write that book, but I love saying yes to everything else!”

For now, saying yes includes the courses he teaches on gardening and landscape design at Edmonds Community College, his radio show on KIRO 710 AM, and his television show on KING 5 — a serious multimedia forum for a man with chronically dirty fingernails.

The goodbye reception that afternoon in the Upper Bunk of the Student Union Building was the winter of SU’s discontent: photo collages and an ivy-iced cake, administrators toasting in hard television lights, a dozen garden staffers with still-soiled knees and game faces. Even Kokie, Ciscoe’s ever-present 12-year-old mixed breed, looked a little hangdog.

“I’ve answered 2,000,043 questions here,” Ciscoe said. “I’ve loved working with students — it makes you less of a geezer. And I’ve planted these gardens myself, planted them and watch them change.

“But of everything,” Ciscoe said, “I’m going to miss the people the most.”

Over 24 years, nearly 100 seasons, the giant Sequoia in the center of campus — “the queen of the Northwest,” Ciscoe calls it — has grown 80 feet.

“That magnolia, Elizabeth” — so close is he to the plants that he names them — “I planted 22 years ago. She looks plain now, but her flowers in the spring will make a grown man cry. And that English laurel on the Garrand Building — doesn’t it look great against the brick? That may have been here in 1891.”

That Ciscoe has a personal relationship with his plants equal to those with his colleagues is testament to his unseemly seriousness and patience. As a boy in Wisconsin, James Morris begged a local priest to let him work in a church’s garden; there, he would take to wearing a sombrero, earning the nickname “Ciscoe,” and would work with an aged master gardener who instilled in him the value of natural gardening — a system free of pesticides and reliant on the balance of nature.

The SU campus he encountered in 1977, he says, was one in need of patience — and ruthless overhaul. Working with limited resources, the young gardener saw gardens overgrown and choked by non-native flora, an environment in radical conflict with the sanctuary he envisioned.

“So we’d sneak in under cover of night and pull out trees,” he recalls.

“Administrators would stop me and say, ‘Wasn’t there a tree there yesterday?’ and I’d just shrug.”

Ciscoe’s patience with university administration — and theirs with his unusual methodology — would slowly pay off, season by season.

“Gardens had to be low maintenance — less than lawns,” he explains. “They had to be beautiful, and interesting in all seasons. They had to attract beneficial insects. They had to feed birds.”

The birds came around, as did the insects. And with them, too, the university administration.

“Everybody climbed on board once a big study found that the number one criteria to draw students was the appearance of a campus,” he says. “Plants are cheaper than people, and the administration’s been really supportive.”

Extra resources for gardening and landscaping has meant an influx of native redtwig dogwoods and white firs, but also the exotic fauna of the countries Ciscoe and his wife, Mary, have visited: Chile, South Africa, France, Turkey, Australia. While the master gardener says diversity means fewer problems, the result has been an informal, imprecise pattern throughout campus — one he believes inspires a sense of safety in nature so profound that one can actually eat from any garden.

“Just here behind the Administration Building, I chew on those rose hips over there, or the strawberries or day lilies. And we have herbs all over, too: parsley and arugula and nasturtium and pansies. I just nibble all over campus.”

Then Ciscoe, a hummingbird of a man, leaps behind a rare Camperdown elm’s grass-grazing curtain of branches.

“Hey look, you can hide inside it!”

In his last days on campus, Ciscoe buzzes around the office he shares with Kokie, who takes sole billing on the door (and in the phone directory) as SU’s “Wildlife Manager.” Kokie, too, has been a campus fixture, as was Goldie, who passed on four years ago — a loss that elicited dozens of sympathy cards to her master. “I think it’s been good for the university to have a dog around. It makes the campus feel like home.”

Kokie sighs and collapses on the carpet at the mention.

“She’s sure gonna miss it here,” he laments. “The begging grounds don’t get much more fertile.”

Around campus, few offices hold the unmistakable odor of fertilizer. Fewer still are periodically overtaken with escaped New Zealand leaf bugs, the four-inch walking sticks that populate a poorly secured aquarium and — to the dismay of some startled blossom sniffers — the gardens throughout campus.

“Have you seen my bugs yet?” he yells, opening the aquarium’s lid. “When I visit the schools,” as he often does, giving talks to students about plants and wildlife, “I put them on my head. The kids just go crazy!”

Beyond their capacity to entertain, the bugs are a vital component of the system Ciscoe and his crew use to preserve the biological balance on campus. Known as Integrated Pest Management, or IPM, the technique uses a combination of methods for pest control: mechanical (washing or squashing bugs); cultural (maintaining disease-resistant foliage); biological (“using the good guys to eat the bad guys”); and, as a last resort, chemical. “I hardly ever spray,” he says. “I have this old trick of using vinegar and hot water on weeds, and that usually does the trick.”

Such natural methods of pest control have earned the SU campus the title of Backyard Wildlife Sanctuary — the only such EPA designation for a public garden. Throughout the campus, miniature “wildlife gardens” draw song birds, hummingbirds, butterflies and squirrels to ponds, waterfalls and an abundance of food sources. “Come spring, people are gonna have to wear helmets for all the hummingbirds!” he says.

Finding the time to get to work on that long-planned book may well prove elusive to Ciscoe, whose schedule even without the mantle of his SU title demands an amphetamine personality: KING 5 TV’s “Gardening with Ciscoe” segment. A weekly garden column for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Regular appearances at the Northwest Home and Garden show, and on AM NewsRadio 710. Features on the “Home Grown Cooking” show and on the HGTV cable network. His informational radio call-in show, “Gardening with Ciscoe,” every Saturday morning on NewsRadio 710. Saturday and Sunday appearances on the KING 5 morning news. A thriving consultation business. Classes taught at SU, the University of Washington Center for Urban Horticulture, and Edmonds Community College.

In addition, he gives some 50 garden talks per year, writes articles for the Washington Park Arboretum Bulletin

and other local green-thumb publications, and sits on several horticultural advisory boards. And did he mention his home garden was featured in a recent issue of Seattle Homes and Lifestyles magazine? Or his regular “Stump the Gardener”

contest sponsored by a local greenhouse?

While on campus, his ever-ringing telephone was less frequently a campus call about a sick-looking elm than a little old lady in Woodinville wondering how to attract hummingbirds (fragrant nettle, honeywort, or fuschia-flowering gooseberry), or a Renton dog owner hoping to clear up brown spots on the lawn (grass seeds, fertilizer, and plenty of water).

“I get tips from people, too — and I test every one of them before sharing them!”

That he’ll be leaving the office behind hardly means an escape from the constant calls; instead, an enhanced media presence (the Seattle P-I post, for instance, came shortly after his departure) means even more questions, more tips—and more chances to share, with a giggle, the joys found in the garden.

Behind every plant is a story for Ciscoe: the prized giant Sequoia, currently at 125 feet, which he once climbed during a storm (“That was a wild ride!”). The rosemary bushes the size of minivans (“I told my wife that in folklore, a rosemary plant means a woman heads the household, and the next day, she’d planted one!”). The Weeping Sequoia, once featured in Sunset magazine and warmly named Snuffleupagus by the gardener for its resemblance to the slope-shouldered Sesame Street character.

Whether they’ll make the planned book is uncertain.

“The book will be about garden design, but with humor — I need to have who I am in there!” And then, with a giggle: “I want to write a book about Seattle University as well, but that won’t be about gardening…”

Without doubt, he says, he will be back, offering tours and visiting the gardens that are less familiar than familial to him —the gardens he envisioned and created, season after season, with his own hands — and the gardeners and landscapers who carry on his work.

“I want to leave a legacy, that in 20 years people look at these gardens and say, ‘Who planted these things?’ Twenty years. You know, if you’re patient, you can get something very special.”