Tracy Collins Ortlieb / Spring Global Business Edition 2020

July 13, 2020

In the past three years, Roberta “Robbie” Kaplan cofounded the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund, filed a lawsuit under The KKK Act of 1871 against 24 neo-Nazi and white supremacist leaders responsible for the 2017 Charlottesville violence, and successfully challenged the City of Starkville’s refusal to permit an LGBT Pride Parade. Her current client list includes Moira Donegan, creator of a widely circulated list of media men accused of sexual misconduct, actress and women’s rights activist Amber Heard in her ongoing legal battles with ex-husband Johnny Depp, and author E. Jean Carroll in her defamation suit against President Donald Trump. Kaplan is further taking on Trump in a separate case: alleging he and his children used their family name to promote sham marketing opportunities to her clients via “Celebrity Apprentice.”

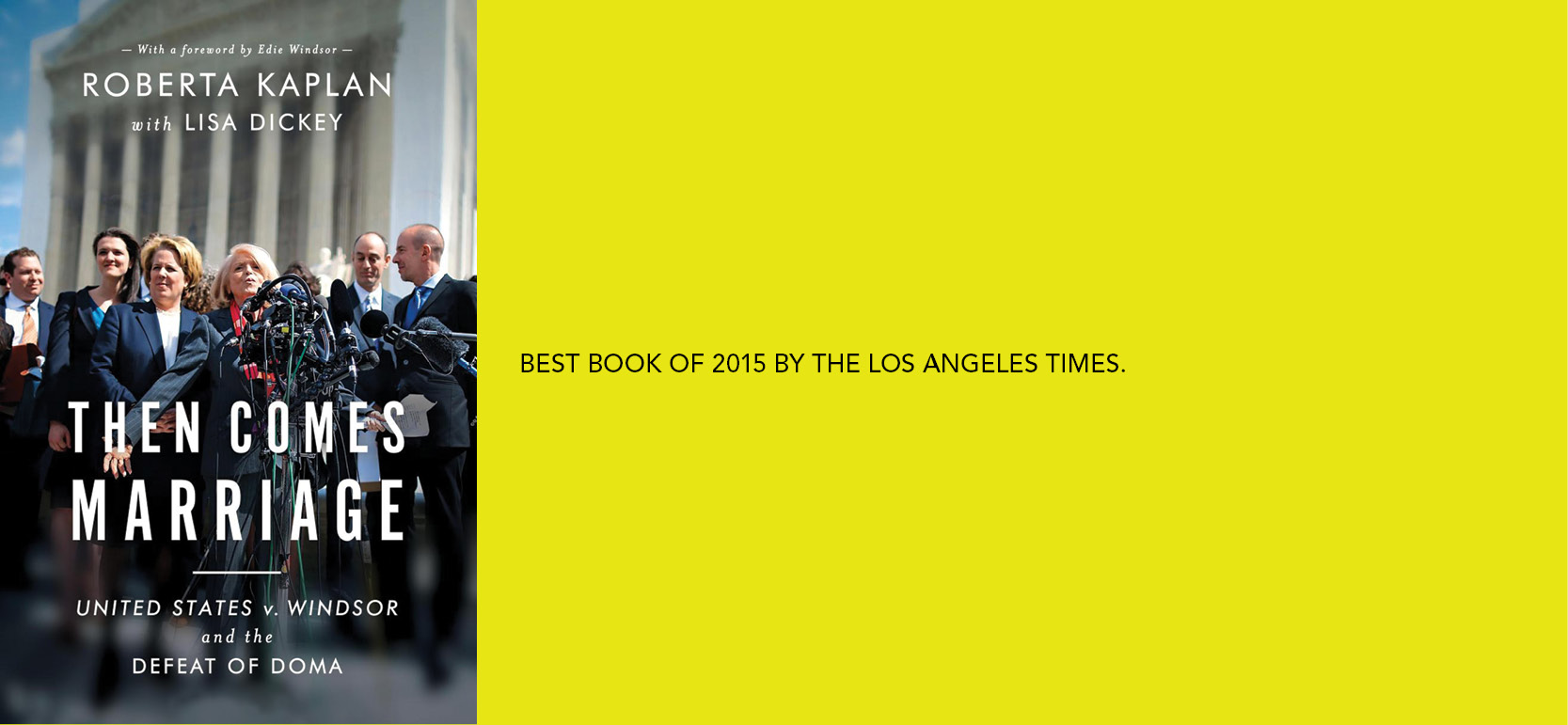

Most notably, Kaplan successfully represented her client Edith Windsor in United States v. Windsor, ultimately arguing the case before the United States Supreme Court. In Windsor, the Supreme Court ruled that a key provision of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) violated the U.S. Constitution by barring legally married same-sex couples from enjoying the benefits of marriage conferred under federal law. The consequences of the Windsor decision were both swift and profound: Just two years later, marriage equality would be enjoyed nationwide. Her book on the experience, Then Comes Marriage: United States v. Windsor and the Defeat of DOMA was named a Best Book of 2015 by the Los Angeles Times.

Speaking with us during lockdown amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Kaplan discussed her background in commercial litigation, how she and her team choose which public-impact cases to pursue, her preparation for and reaction to the Supreme Court victory, and how feminism guides both her case selection and the ethos of her firm, Kaplan, Hecker & Fink.

What compelled you to start taking on public-impact litigation?

The Windsor case fell in my lap in a lot of ways. There was just pure happenstance that Edie Windsor had gone to some civil rights organizations, been turned down, and then a friend of mine who’s a legal headhunter knew her and called me. I think one of the most important things to know about life is when that happens, you should take the opportunity.

It was pretty clear to me within a couple minutes of meeting her that she’s actually the perfect plaintiff to help establish the principle of it: Gay couples are entitled to equal dignity. It was so clear to me that her story and her case and the damage she had suffered to the tune of $363,000 was something any American would understand, and it was the perfect vehicle to challenge this statute.

For an attorney to argue before the Supreme Court is equivalent to becoming an Olympic athlete. How did you prepare to argue the case, and how did you respond to winning it?

I prepared for it with just enormous amounts of anxiety. We essentially went through the legal version of basic training. Once the briefs were in, we spent about three months between that and arguments, and we spent that time doing about eight formal moot courts: one at NYU, one at Stanford, one at Georgetown. And then we did probably five times as many informal moot courts.

The goal was just to practice, practice, practice. By the time we got to the argument, there probably wasn’t a single question that I was asked that I hadn’t practiced dozens of times in the room. But when you’re arguing it at the Supreme Court [level], everything is happening in such warp speed that you almost have to have those answers in your muscle memory; you don’t have enough time to consciously consider various alternatives.

Immediately after the argument, the overwhelming emotion I felt was just relief. It was, “Thank God I didn’t screw this up,” because I felt such enormous weight on my shoulders arguing this not just for Edie but obviously for so many people who were going to be affected by the decision.

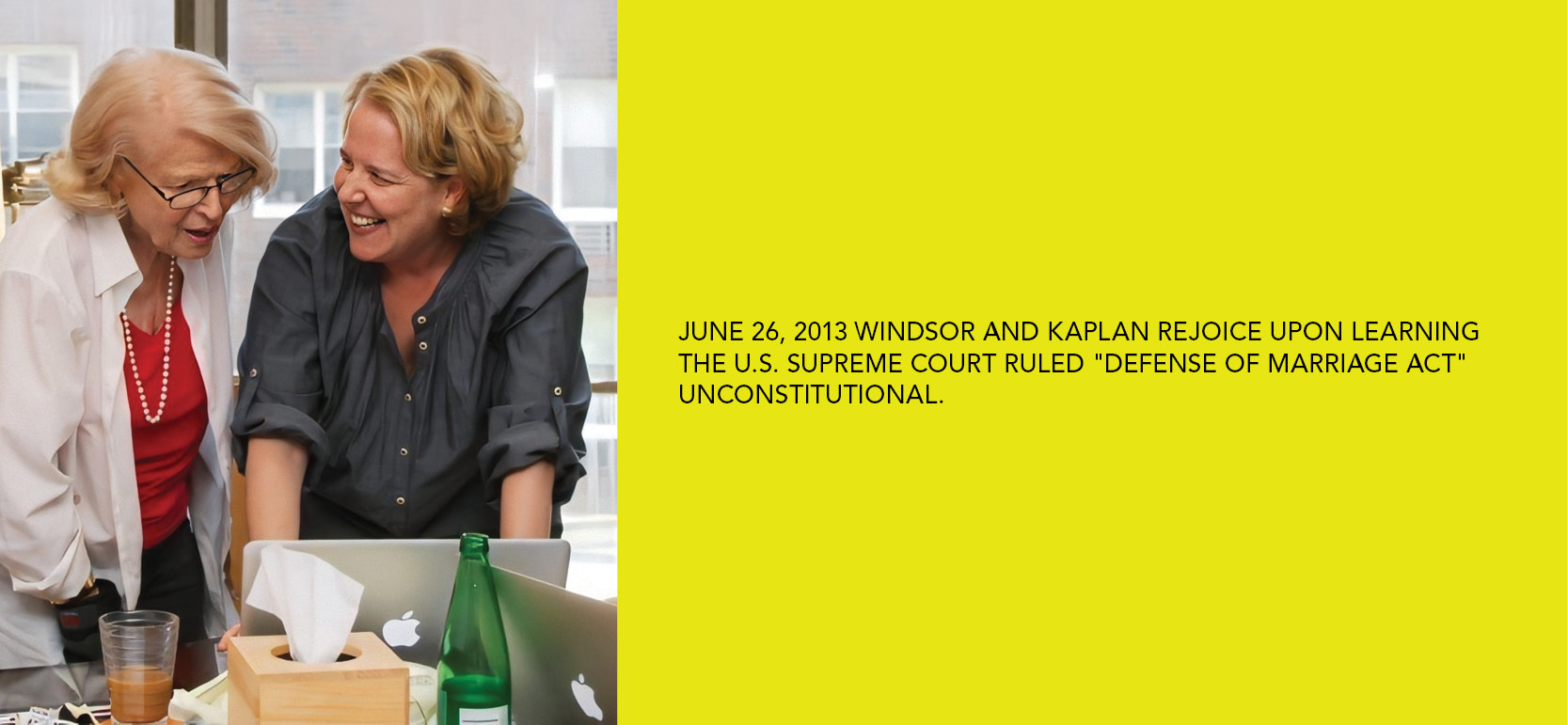

When that came down three months later, it was just elation. We were with Edie in my apartment, continually refreshing the screen on SCOTUS blog to see when it was coming down. When we saw that it was a decision by Kennedy and that Scalia had dissented, we knew without reading another word that we had won, and complete pandemonium broke out.

Talk to me about how the case against the Charlottesville neo-Nazis came about.

That’s another story of pure happenstance. I had only recently started my firm and decided from the very beginning that [it] was going to have a very strong commitment to public interest. The Monday after [the Charlottesville incident], I decided that we should watch some of the press coverage during lunch. In retrospect, that was a mistake because I didn’t realize how upsetting it was going to be; we saw the paralegals leave the room crying because it was so disturbing. Watching what had happened on the streets, the first thought in my head was, “Something needs to be done about this.”

I was concerned that the then-attorney general, Jeff Sessions, would not use the resources of the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice to do that. I started to think right away, “What could be done?”

I called courts and law reporter Dahlia Lithwick, who was living in Charlottesville, and said, “I have this idea. What do you think?” She said, “It’s a great idea. I will introduce you to some folks down here.” We were in Charlottesville within about 78 hours of that call. The city was in a state of shock; people were still scared of these guys. [We] were quickly able to select the plaintiffs in our lawsuit and file the complaint at lightning speed.

One enormous lucky break we got was that a group of hackers called Unicorn Riot had hacked into the servers that the organizers of the violence used to organize. Because all these messages were hacked, we had precompiled discovery to a degree I’ve never experienced. We used those communications for two things. One, to unmask the leaders. We didn’t want to sue everyone or anyone; we wanted to sue the people who were truly responsible: the groups and individuals responsible for organizing this and for planning the violence, implementing the violence, and celebrating when it had happened. And two, how did they do it? What did they say? How did the planning work? We laid that out in a complaint which reads a bit like a horror novel.

Getting discoveries has not been easy. One of them has been put in jail for three days for contempt given the discovery problems. But we are much farther along, and we intend to go to trial. We have a trial date of late October.

Since the election, the #MeToo movement exploded across the American landscape. Can you tell me about the origins of the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund?

In Los Angeles, as #MeToo was heating up, there were a bunch of women, mostly in the movie industry, who started to meet informally to talk about what was going on in light of the allegations about Harvey Weinstein. They’re very smart, impressive people and were determined that—unlike in times in the past—they were finally going to do something about the industry’s sexism, discrimination, and abuse that would actually have real impact and difference.

Together with Tina Chen, the Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund started because we realized that there were at least two problems out there. One, in harassment cases, it was not economical for most cases to be brought by lawyers. For many women in working-class or low-level or middle-management jobs who are harassed, how do we get them lawyers? Is there a way that we can re-incentivize the market to find lawyers to do that? And secondly, how do we deal with people like Melanie Kohler, who got sued by Brett Ratner, had the courage to speak out, did it only on her own Facebook page, and was a scuba-diving instructor with no ability or resources to defend herself?

It’s a huge organization today, and I’m honored to serve as the chair of the board. We’ve come a long way, but we’ve got a long way to go.

Between Moira Donegan’s Media Men list, your representation of Amber Heard and E. Jean Carroll, and your prosecution of the Trump family for fraud in the Southern District of New York, you’re ubiquitous in progressive case law. Given your work on cases like these, particularly when taking on the Trumps, has you or your team faced any harassment?\

The short answer is there have been threats. Obviously, the most violent of those threats was the Charlottesville case, where we made a motion. If something good can be said to come out it is that one of the reasons we’re so far ahead in being prepared to shelter in place for COVID-19 is because we had to deal with all these security issues in connection with the cases that we’re in.

“The most important thing to do in your career as a lawyer is to go with your gut.”

How important is it to you that Kaplan Hecker is women-led and what message does that send to other women attorneys and aspiring attorneys?

It’s extremely important to me and to all of us, including my male partners, to be honest. We are dedicated to walking the walk and talking the talk and making sure that our firm is different in terms of how it treats women, respects diversity, and gives people who have not been leaders in the profession real chances to be leaders.

Particularly today, how would you advise other attorneys to better take on issues of social justice?

The most important thing to do in your career as a lawyer is to go with your gut. And when your gut tells you that a case is the right case to bring, bring the case. After all, we got Windsor. Most people thought that was not the right case to bring. When your gut tells you that the place where you’re working is not the right place to work, go work somewhere else. When your gut tells you that you’re not working with the kind of colleagues you want to be surrounded by, find better colleagues.

Women have been risk-averse in the legal profession. Women have a lot more to lose, and they’re more conservative because of all the endemic sexism in the world. The one lesson I would say to people, especially to women is, sometimes, you have to take the chances and go with what your gut, heart, and mind tells you about which ones to take.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Published in Best Lawyers Magazine, 2020 Spring Global Business Edition